Article

UI/UX Principle #16: Use Affinity Diagrams to Collaboratively Clarify Fuzzy Data

The definition of affinity is “a similarity of characteristics suggesting a relationship.”

Affinity diagrams can be used as a brainstorming tool, allowing a group to codify ideas, hypotheses, and predictions. They also allow teams to gather observations and feedback about usability, organize the information to identify themes and patterns, and create a custom data classification scheme that can be used to determine actionable next steps. Additionally, affinity diagrams are a tool that allows a design team to take into account the primary pain points, concerns, and needs of users, and they aid in creating detailed and accurate personas.

Used to find meaningful patterns in qualitative data, the affinity diagram method can be implemented in a variety of ways and at different key points of the design cycle, such as when:

- An internal team wants to solicit ideas and consensus about how to organize a body of information

- A working version of a product is being tested for usability

- Data acquired during user research is being analyzed and categorized

An Evolution of Empathy

Affinity diagramming, as a tool applied during user research, is an exercise in empathy. The method creates a relationship between data and its implications for UX.

Forming a hypothesis about how to alleviate user pain points is a logical starting point, but a hypothesis runs the risk of removing the focus of the design process from the end user; it’s based on an assumption rather than an intimate understanding of user needs, desires, and behaviors. However, once investigation begins – once the hypothesis begins to be tested – evidence validates or invalidates it, allowing the supposition to evolve into something more sensitive to the personal stories of the user base.

Organizing user research data is essential. In order to create human-centered designs that foster meaningful user experiences, the process of classifying data needs to take place in such a way that the focus remains on understanding its implications and applying it appropriately. The primary focus, as in all aspects of user UX design, should be on the end users – the people who the implications of the data will ultimately affect.

Finding Value in Fuzzy Data

Contextual inquiry can take the form of an interview conducted in the user’s natural environment (workspace, home, etc.). A user researcher watches users complete a task, asking clarifying questions to probe deeper into their thought process, recording observations about behavior. During the process of analyzing a given task, researchers might guide the interaction back to important user actions that fall within the scope of the product the team is creating or features of the existing product they are trying to improve.

Contextual inquiry gives researchers what Extractable calls “fuzzy data”:

“At the start of the design process, it can be difficult for designers to conceive design direction from fuzzy data and requirements. The term ‘fuzzy data’ can have multiple meanings to different people and industries, but in the context of UX Design, it is all the known information related to a project that is nebulous and not yet actionable.”

The quote from Extractable about what they term “fuzzy data” reveals a crucial benefit of affinity diagramming: it allows researchers and designers to take indistinct information and make it concrete and actionable.

Say a researcher is testing a customizable geolocation app that allows users to search for nearby mobile businesses. A researcher would have a difficult time making a general design recommendation based on an observation that “One participant attempted to filter her search results when asked to complete the task of using the search function to find more information about a local business.” But if that observation was compared against similar findings in other contextual inquiry observations, and the findings were aggregated and grouped thematically during an affinity diagramming session, the decision to add additional search functionality would be substantiated.

4-Step Affinity Diagramming

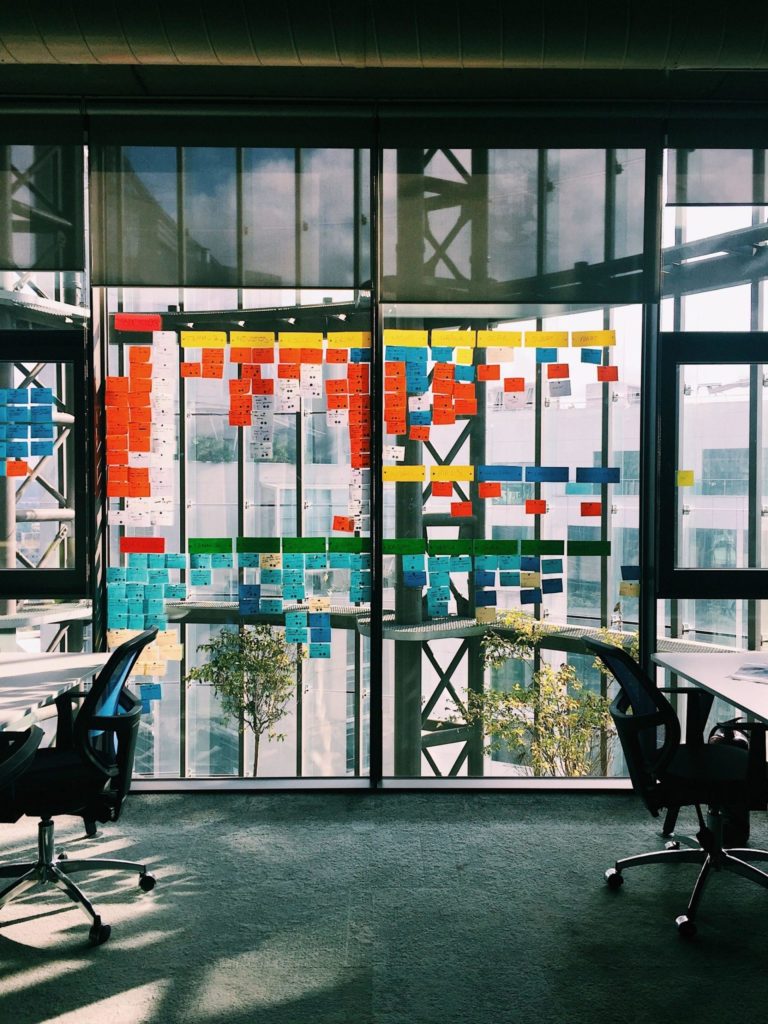

It’s a best practice for affinity diagramming to be done in complete silence – that way, equal weight is given to both the louder and the quieter voices on a design team. The process can work like this:

- The team commits all of the qualitative data points to Post-It notes, of which there can be dozens

- The team posts all of the transcribed data to a large whiteboard, which enables the Post-Its to be manipulated

- The team, in a pre-designated “timebox” – 20 minutes, for example – organizes the data thematically based on the general insights it suggests about the different parts of a problem

- The team continues to organize (and reorganize as needed, if there’s any disagreement) the individual points into meaningful categories until the end of the timebox when, ideally, all designers come to a consensus on the most important recurring themes in the affinity diagram

If consensus isn’t reached during the silent timeboxed portion of the activity, discussion commences about how to more accurately organize, categorize, and label the qualitative data points so that all members of the design team are in agreement.

Once consensus is reached, each category should be summarized with a more general, all-encompassing “I” statement from the perspective of the user. In the earlier example of the mobile business app, a statement would be “I find specific businesses by using a filtered search.” If enough members of the user base articulated some variation of the fact that they desire a search filter function, then the design team could make a collective decision to spend extra time focusing on redesigning the search function to satisfy that important user need.

Given constraints such as time and budget, articulating the importance of design modifications to key stakeholders can be difficult. Data produced from affinity diagramming can be used to justify these decisions.

While affinity diagrams can give specific micro insights into what elements of a design the team needs to focus on improving – such as the nuts and bolts of search functionality – they can also reveal larger macro user stories about the hopes, dreams, and aspirations of the target user base, which can in turn lead to design decisions that have significant impacts on branding, conversion, adoption, and customer loyalty.

Delivering Data

While qualitative data is very useful, it has the tendency to be concealed behind vague observations or free form responses to survey questions. Because the qualitative data – which can be just as rich and illuminating as quantitative data – is hidden, it’s tempting to minimize it and the potential influence it can have on a design.

But these qualitative data points can bring to light the pain points, positive experiences, and end goals of users when interacting with a specific product feature. And paying attention to that information leads to good design. By only paying attention to quantitative data, a team runs the risk of overlooking paradigm-shifting insights that could move the needle of a product from being acceptable to being exceptional.

The meaning that arises from affinity diagramming is deliverable. It can be used to make calculated estimations which lead to firmly grounded hypotheses, which in turn lead to the ability to make lo-fi wireframes that can be tested again to inform the final iterations of a design.

Conducted in a workshop setting with nothing more than Post-It notes, writing utensils, and collective brainpower, affinity diagramming is a UX research and design tool with a very low cost and a high return on investment.

Affinity Diagramming at Fresh

At Fresh, we use affinity diagrams as a UX research tool for:

- Personas: By taking time to organize data and implement insights about users, we create meaningful personas that then inform user stories and story maps we utilize later in the design process

- Information Architecture: In order to sort through and organize robust data sets, we use affinity diagrams, leading to logical layouts and intuitive interaction design

- Discovery: Unveiling insight from stakeholder and user interviews requires focused collaboration and critical thinking – affinity diagrams aid in the process, allowing our team to manipulate and catalog data in order to create a shared understanding of its implications

This simple tool brings high value to the design process, and due to its utility and effectiveness, we strongly vouch for the importance of affinity diagramming in the design process.