Podcast

The Future of Recycling

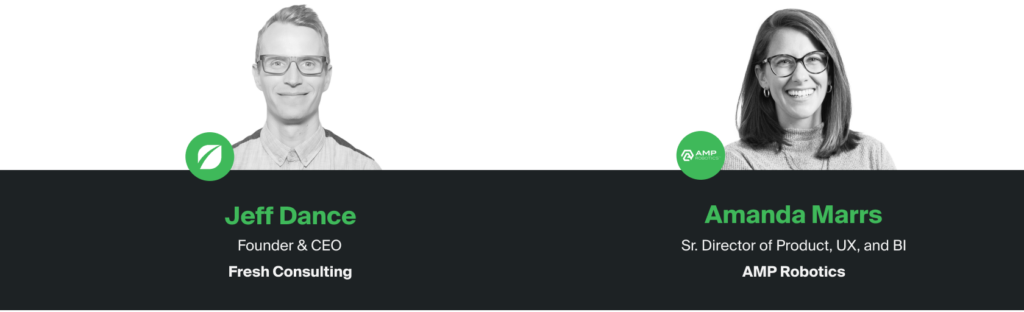

Amanda Marrs, Sr. Director at AMP Robotics, reveals how AMP is developing high-tech waste recycling solutions to help create a more sustainable future. Jeff and Amanda take a glimpse at the waste recycling industry—touching on everything from the process of recycling materials and promising technology to international trends and logistical challenges.

Amanda Marrs: I was helping volunteer at a race a couple of months ago and there was no recycling for all these plastic and aluminum cans, and so I held up a bag and had every runner drop their item into my bag and then took it home and recycled. So it’s the sustainability level I’m at. I think that’s like a level of four to five, maybe. There’s more I could do.

***

Jeff: Welcome to The Future of, a podcast by Fresh Consulting, where we discuss and learn about the future of different industries, markets, and technology verticals. Together we’ll chat with leaders and experts in the field and discuss how we can shape the future human experience. I’m your host Jeff Dance.

***

In this episode of The Future of, we’re joined by Amanda Marrs to explore the future of recycling. Amanda, we’re so excited to have you in touch on this important subject about our future together.

Amanda: Thanks, Jeff. Happy to be here.

Jeff: Yes, It’s so exciting. Garbage is such a big issue. We know recycling is a huge part of that answer. I was reading recently that there’s 2.2 billion tons of waste produced each year and obviously a portion of that gets recycled, but I get the perspective of that. The comparison is 1 million tons is close to three Empire State buildings, so we’re talking about thousands of Empire State buildings of garbage each year. This is such a big issue for our future, so I’m really excited to chat with you, and learn more about your experience in the garbage and recycling space, really the sustainability space.

Can you tell the listeners more about your background, a little bit more about yourself?

Amanda: Yes, absolutely. I am a senior director at AMP Robotics, and in my current role we make trash robots. So it’s AI-driven robots to sort recycling off of moving belts. When you put a recyclable in your blue bin, it goes to a material recovery facility and that’s where our technology lives to help sort those into the right commodity items. Prior to AMP, I spent some time at GE working in a host of smart grid solutions, so that was my first sustainability product. Had a variety of roles at GE, all in electrical distribution roles, and then I went to Amazon for a period and worked in logistics, so now I’m recycling all the boxes that I used to ship out at Amazon.

Jeff: Amazing. It’s a cool career so far, and I noticed also you had a master’s degree from Stanford. What type of master’s degree was it?

Amanda: Management Science and Engineering.

Jeff: Nice. Then an undergrad in Aerospace Engineering as well, so all that engineering leadership. How did you become a sustainability nerd, a recycling nerd? Tell me.

Amanda: I think it actually started in my first aerospace job after college. I started a recycling program in the office. There were only five of us, very small office, but I just couldn’t stand seeing all these aluminum soda cans getting thrown away so I used to collect them and take them to the recycling center down the road myself. Then that inspired me to go to grad school at Stanford and focus on energy and environment, and how can we start to bring improvements anywhere it’s needed in that supply chain.

Jeff: Amazing. Tell us a little bit more about AMP Robotics. We want to talk about today and the future, but AMP robotics seems like such a fascinating company. Tell us more.

Amanda: Yes, I think it’s fascinating too. AMP Robotics started in 2014. Our founder and CEO is Matanya Horowitz. He has many degrees, but amongst them is a PhD in robotics. Back in 2012 to 2014, he was looking around at the new technology that AI could bring and he was looking around at where this could really help the world. So he looked at a number of different opportunities but came across the waste industry and everyone told him, “There’s no way you can apply this technology to the waste industry. Things are really messy. It’s going to be really hard to detect what’s happening.” I’m pretty sure he said, “Challenge accepted,” and then he started AMP.

It was a lot of dumpster diving and a lot of figuring out how do we first apply the AI identification to be able to say this is an aluminum can, this is a plastic water bottle, specifically what polymer of plastic is it? Then putting it together with robots. We started with a side-to-side robotic entry robot and made many modifications from there, and now we use a delta-style robot, it can move in many different directions with quite a lot of speed and quite a lot of force.

Where we are today, fast forward from 2014 to 2022, we have over 250 robots installed and being used across the world. Our primary customers are located in North America. We’re based out of Colorado, so North America is our primary market. Also different countries across Europe and Asia Pacific. We apply this technology in a few different vertical markets for recycling.

The primary market is your material recovery facilities for single stream recyclables. That’s what we throw in our blue bins. Another one is the organics industry, specifically pulling out contaminants from organic streams so that that can go and get composted correctly. Then the third is construction and demolition, because everything becomes end-of-life at some point. We also do apply our technology in electronic scrap recycling as well.

Jeff: Very cool. I think sometimes it’s rare to find a really interesting company that also has such a strong mission around sustainability. When you see organizations that are actually for profit, and can sometimes even move faster than maybe a nonprofit would, I think it sounds like a great company to be part of.

Amanda: It’s fantastic, full of very passionate people who care both about the technology and also about making a positive impact on the world with that technology.

Jeff: I love it. I heard you mentioned the mission, what was the mission of AMP?

Amanda: We envision a world without waste, and we use technology to enable that.

Jeff: Nice, let’s dive into that. First, let’s talk about today. Tell us more about the problem with garbage today.

Amanda: Big problem. I mean, those numbers you threw out at the intro are absolutely the right magnitudes. Breaking that down on an individual level, in the US, according to 2019 EPA study, we generate 5 pounds of waste per person per day. I’m going to let that one soak in for a second. 5 pounds of waste per person per day. It’s just one of those things that’s all of our problems to solve. It really sets the stage for how much this will continue to grow as population grows.

Also, as just material packaging continues to be something that is waste. For some context, historically, in the ’70s, we were at about 2.4 pounds of waste per person per day, so you can see an increase over time. That trend is expected to continue as well as population increase. We’ve got to figure something out.

More than just the feel-good sustainability piece of it, these are materials, these are commodities, and so there is a part of global supply chain over the last two years, I think we’ve all gotten a crash course on it. This is really a part of a circular economy. These are commodity items, they have inherent value to them. If they’re just ending up in a landfill, they’re not doing anyone any good as far as the value of the material, and now you’re adding the environmental impact of it, and it’s just two negatives.

Jeff: It’s insane. Basically, I’d be carrying around every week, 35 pounds if I would put that on my back, of garbage. That’s the average garbage per person.

Amanda: That’s just waste at end of life. I mean, 35 pounds is my week-long backpacking weight.

Jeff: Tell us more about the recycling industry, having commodities that there’s an economy attached to this, tell us more about how this works.

Amanda: For sure. Let’s take an example, I have a wonderful prop here, of a plastic water bottle. This is something that we use, we enjoy the benefits of it as a consumer because it is lightweight, saves some emissions from transportation. There’s good things to plastic, I don’t want to just say plastic is terrible, plastic is just not easily recovered. We use a product, we’re done with the product, we as consumers really enjoy the convenience of now just tossing it out. When you toss it into your blue bin and it gets picked up, it goes to a Material Recovery Facility, or a MRF.

At that point, it goes through a series of sorts, these are really large buildings. It’ll usually go through first a pre-sort, where people are pulling off stuff that’s not supposed to be in there. There’s a term we like to use in the industry called “wish-cycling,” people wish it was recyclable, so they throw it in there. It’s not, please don’t, but it actually really messes the systems up, and costs a lot to take that out. First is pre-sort, pulling out the stuff that is going to mess up the machinery.

Next is typically a cardboard screen, it’s called OCC, it stands for Old Corrugated Cardboard, and this is the cardboard that now gets popped down and turned into new cardboard. Your big pieces are going off the top of this just mechanical rotating screen, and that’s also where you get 2D, meaning paper, and 3D, meaning containers, separation. Then you’ll go through a series of sorts for each of those, for 2D and for 3D, to separate out into different commodity types.

Within your paper stream, you’re looking for things like sorted off as white paper, super high value can get turned back into paper really well. Newspaper, also valuable. For your containers you’re looking at things like your valuable plastics. The plastic number on your water bottle, or whatever the thing is, tells you the polymer type. Those get separated into polymers or into blends, depending on where they’re going for offtake. Your metals, so your aluminum cans, which are UBC, Used Beverage Cans, those get separated out.

What you’re really doing is trying to sort out everything into the commodity where it has an offtake. This is where recycling starts to get a little tricky for us as consumers. What your offtake is and how recyclable something is is directly related to where you’re located and what the offtake in your community is. If you’ve got a Trex decking who can take your LDPE, your low density polyethylene, your thin films and your plastic bags, cool. Your community is going to want those. If you don’t, hey, that’s actually not recyclable in that community. This is why you get so many different things of, different instructions as consumers. Do you recycle this or not? It really depends on where you are. What is the recovery rate? Really depends on where you are.

Once everything gets separated into the commodities for offtake, your plastics will go to plastics recovery facilities and they will continue to sort and refine. We’ll get back to this example of a plastic water bottle. It also has a label on it and it also has a cap on it.

Those are different polymer types that you have to separate out. So depending on if it’s a chemical recycling process or a mechanical recycling process we’ll change what they do with it. Ultimately, you’re trying to get back down to a plastic pellet that can be reused.

Jeff: Got it. You are supposed to take off the caps. That helps the sorters.

Amanda: The more you can get things into their single polymer, the better. That’s ultimately what’s going to happen.

Jeff: Got it. Thanks for this education.

Amanda: No worries.

Jeff: As far as recovery, you mentioned it depends on location, but what would be an estimate for different states?

Amanda: Some states are 15%, some states are 85%. There’s such a wide range.

Jeff: So some states have a lot of work to do.

Amanda: Some states have a lot of work to do.

Jeff: Makes sense.

Amanda: We’re here to help them.

Jeff: We’re all wishing in some sense when we throw things into the recycling bin, but it depends. One thing that really changed the game as I understood it was China’s policy in 2018, I think they called it Operation National Sword, where they said, “Hey, we’re not taking more garbage, more recycling,” being a major- the number one importer of the world’s recycled goods. Tell us more about that and help users understand how that changed the economy a little bit.

Amanda: For sure. Being a commodity market, it is driven by the economics behind it. You have a cost for transportation. Me being the sustainability nerd that I am, I’m quite happy that we’re not spending the emissions impact on the world to move waste halfway across the world. A huge fan there. It forces us to figure this out domestically.

You have your cost of your sortation, your cost of your transportation, and then now the value of the commodity that we can make. The shift of having to figure this out domestically has really forced us to figure out now how do we make bales of good value? How do you increase that value? How do you drive your cost of sort down so that the margins are now making this a viable economic business? Really, it’s a business.

Jeff: In some sense, it sucks for businesses that were selling these recyclables. Their value has gone down. In another sense, it’s created a domestic need to solve, deal with our own waste essentially. As we create the infrastructure to deal with that waste, prices should go up because we’ll be able to reuse those commodities. In the long run, it could be a good thing. The National Sword could have been a good policy for the rest of the world, but there’s also short-term pain there.

Amanda: Yes, absolutely.

Jeff: Makes sense. Any other thoughts on the challenges with garbage and recycling today, before we move into the future?

Amanda: You and I are part of the challenge. What I mean by that is really every consumer, it’s really hard to drive consumer behavior. I saw this back in my energy days with things like Smart Grid and how do you start to get people to opt into time-of-use pricing programs or demand response programs where during the hottest summer afternoons you’re not using your AC or you’re not using things that require energy so that it’s not a draw on the grid.

It’s just proven time and time again across various sustainability initiatives like that one and recycling, it’s very hard to drive consumer behavior changes. We are such a convenience-driven society. The more we can really look across the board, across those 5 pounds of waste per person per day, what are the things that we can permanently replace, temporary single use packaging, specifically plastics?

Jeff: I’m glad you mentioned that we’re a big part of the problem today. Obviously, there’s so many pieces of this circular, hopefully, circular economy. There’s the government, there’s the companies themselves, there’s the companies that make the products, there’s us as consumers. You mentioned the economics associated with all this as well. I can see why it’s a challenge, why it takes time, why it takes a coalition and a lot of work across the board to move the needle, but we need people like you to help us do so.

First, let’s touch on the future a little bit. You mentioned the AMP Robotics’ mission was a world without waste. As we think about the future, 10 to 20 years from now, how do we get there? What do you envision in the next 10 to 20 years?

Amanda: My north star vision and my dream is that we actually do have a world where everything is first designed for circularity, so designed for composting, designed for recyclability, designed for circularity in the packaging, so that you and I as consumers aren’t bearing the burden of how do I end of life this product that I’ve just enjoyed the convenience from it. To do that, it takes a lot of data, it takes a lot of economic incentives, and it takes a long period of change. So that really goes back to how is the government through structures like extended producer responsibility, driving the reporting requirements, and from data comes system-wide change.

How does that hold consumer packaged goods companies accountable? You and I don’t have a choice when we go to the grocery store and we want to buy blueberries, for example, they all come in thermoforms. That’s just how they’re transported. That’s the best thing for reducing your weight during transportation, which reduces emissions. That’s why I don’t want to say plastics are awful, they bring us a lot of savings for sustainability initiatives in other places. We don’t really have a choice for “Now what do I do with this packaging?” I think that goes back to now the packaging producer and what they do to design that for recyclability.

That’s the first part of the value chain is around that circularity of the packaging.

The second part where we play is around the sortation. If we can see it, we can sort it. We can see it because we have AI and the benefits of this technology and how that’s grown over the past decade. Things like the GPU cards becoming cheaper and faster, thank you gaming industry, helps with things here, so very cool.

Then the last part is the offtake. You can have the packaging, you can sort it, that’s all great, but now what do you do with it? How do you turn it into something different? When I envision that, that north star vision of the perfect world, it’s that whole value chain, everything has a place it can go, everything can be sorted and everything ends up in a reuse state.

Jeff: Nice. As far as that first piece, you mentioned designing, and part of the purpose of this podcast, all the podcast sessions that I’ve done, is how do we design the future with more intent? Technology often changes so fast. Things are changing so fast that if we can design things with a little bit more intent, then the future can change, and we might catch some behaviors that would be better off had we put more thought into it versus just gone with how the change has gone, and especially with technology in the last 20 years it has life of its own. It’s really changed just as humans and humans haven’t adapted as fast as technology.

Think about this space. Are you aware of guidelines for designing products with more intent for recycling? Is that something that exists? A company like us that actually designs mostly hardware products, we build robots, but we actually do get involved sometimes in the packaging of the products that we design and build as well. Are there guidelines for this?

Amanda: Yes, there are some, the TLDR. So the summary of it is, as much as you can make things separable into their different commodity items and make sure it is a commodity that can be reused. The things like cardboard, aluminum, those are things that are easily reused and have value in the market.

Jeff: This space is such a cool space to be in because of the benefit. What other technologies might play a role in the future of recycling? Is it more and more robots? Tell us more about technologies that you think could be influential.

Amanda: For sure. That sort piece, you need a touch to sort something, similar for a logistics network, you’re touching a package to move it. If you put on a lean manufacturing perspective, you want your single touch and you want it to be the most efficient way to move something from A to B.

When we think about how do we help enable those sorts through our technology, we look at what locations in that facility need that touch? That’s the best place for the touch. What’s the right way to efficiently recover that material? If we’re going after a material, we’re getting it, we’re making sure we’re not wasting picks. Then how do we make sure that we’re expanding our sortation portfolio to go after as many different material types as possible?

Shameless plug, we just released a new product a couple of weeks ago called a Vortex. Our primary robot is called the Cortex so we really like our naming convention here at AMP.

The Vortex is focused on thin films. If you think about those puffy things that keep your objects in a cardboard box from moving around, so the stuffing in a box, that is all thin film. You take the air out of it and it’s just like a plastic bag. Anything like that gets tangled in machinery, becomes contamination in fiber, which now reduces your value of a fiber bale.

Film is a problem in this industry. Unless you have something like a truck stacking offtake for it, what do you do with film? That’s what Vortex is designed to, first and foremost, pull out these contaminants, help the rest of the machinery have good long life, not get messed up, help your fiber maintain its purity but now also, if we’ve driven the cost of the pick down, we now are being cost-effective at creating a film bale that when that can be used, wonderful, and bringing back really the commodity value of film.

Jeff: Interesting. I appreciate that specific example. I would assume that as you multiply that, specific machines to pick specific things, you can increase the quality and the purity of the commodities.

Amanda: Exactly.

Jeff: That’s great. As far as the circular economy goes, this being trying to get to a circular economy, and this being a complicated problem that’s beyond just one company, what are some other things you think that need to happen from a macro perspective to spur this along, knowing that we’re not quite there from a circular economy yet, or we’ve seen how disruptive it can be when a single country says, “Hey, I’m not going to import this stuff anymore?”

Amanda: Yes. Data, data, data. I think you can’t make large system changes without really having a picture on what’s going on so that you can make the right moves for what needs to happen. When we think about this industry before technology was brought to it, you had manual sorters, and you would have to do manual audits if you wanted to get some characterization of the material on your belt but those would be snapshots in time. Those wouldn’t be really showing you how things are trending and differences with things like Christmas time we see a lot of differences in the waste stream.

By the way, your Christmas lights are not recyclable please, bring them to an electronic scrap recycler, but do not put them in your blue bin. That is a problem during Christmas time for us.

Jeff: You call it wishful recycling, right?

Amanda: Wish-cycling yes.

Jeff: Yes.

Amanda: Exactly.

Jeff: I think we need bins just for electronics. The E-waste is such an issue, right? Wouldn’t that be beneficial?

Amanda: That’s an interesting one. Yes, you’re right. It is so much bigger than it used to be. Every location tends to have someplace that you can drop off electronic recyclables for free.

Amanda: Yes, so please do look that up in your industry listeners. [ . . . ] When you had manual sorters, you really could not understand what was going on seasonality, any given time, relating back what composition you saw from what hauls, which helps you understand how to go, maybe educate your consumer base in that area, if you are getting a lot of Christmas lights in one neighborhood or something. Data really helps drive local changes, but it helps when you start to aggregate it to look at what are some of the national trends, and what are some of the things that we could do for that.

That also now helps feed consumer packaged goods companies and what they want to do. We’ve been working with some wonderful large companies that are looking for how can they detect their specific goods in this waste stream so that they can really look at how do they recover it more. It’s really great to see these corporations wanting to stand behind their sustainability goals.

Then extended producer responsibility. How does government help create incentives, whether they’re carrots or sticks to really force change. That’s really, every system change is going to come down to what are the economic incentives for it, whether it’s carrots or sticks.

Jeff: That’s interesting. Obviously, with what we saw in China, that huge disruption in such a short period of time, you can see how the carrots or sticks can make a big difference. That’s where I think this gets bigger and obviously more complicated to move the needle.

To summarize, if we think about the next 10 years, it’s more about infrastructure, data, lots of data, data, data, and more machines that can help with the sorting aspect, the designing aspect where things can be more recognizable, where companies are actually helping you with that. Then from there, maybe 20 years from now, it’s like we truly have a more domestic circular economy where we get these higher thresholds of usability when we’re doing all the wishful recycling essentially. Maybe our wishfulness gets better essentially?

Amanda: Yes, for sure. 10 years is data is driving immediate change on what we can produce and what we can sort. 20 years is that packaging. There’s the three parts of the value chain: the packaging, the sortation, and the offtake. Packaging is changing, sortation is now a solved problem which is so wonderful, and it really couldn’t have been solved in this way before we had the technology to recognize, you got to see items to sort it, right?

Now, the offtake piece is a huge part of a lot of academic research going into, how do you make better use of these undesirable materials that don’t inherently have good value, aren’t highly recyclable, what do we do with them?

Jeff: Are you aware of other companies or even maybe even other countries that are really moving the needle as we think about the transition that we all want to see?

Amanda: Yes, for sure. In Europe as a region, there are more extended producer responsibility schemes in place, and have been for a while. There are also bottle bill programs in place depending on the country. It is leading to more of a consumer response to recycle items and then relay the reporting. So that 10-year vision that I have for the US, we’re getting there, we’re catching up. That’s really cool to see it in practice, and now it’s a matter of scaling it beyond where it is.

As far as companies, I know I mentioned that we were working with some consumer packaged goods companies, and I can’t mention who, but it’s been very exciting to see large brand names really stand behind their corporate sustainability goals and really say, “We want to figure out how to keep this from getting in the ocean. We want to figure out how to recover this,” and working with us, first, to train our AI to detect their various packaging, and then next to figure out, now, how do we have the most effective sort for it.

Jeff: As far as the everyday advice that you would give someone, what are some tips that you would give to someone on their everyday? You said we’re part of the equation, so as a sustainability nerd tell me what I can do better.

Amanda: Well, first and foremost, take a look at everything that you use, specifically things that are single use, and just decide for yourself, is there a change that you can make there? That’s a personal decision for each of us. For me as my home products, my cleaning solutions and my toiletries started running out, that was the moment where I said, let me go figure out if there’s a better alternative. Things like using washing sheets rather than liquid detergent, using wool dryer balls with scented essential oils on it rather than dryer sheets. Those are changes I’ve decided to make for myself. It really just starts with, what are some of the lifestyle changes each of us want to make to help reduce that waste.

The other thing we can do is for your favorite brands, get involved in contacting those companies and asking them to create more sustainable packaging so that we can still enjoy the product, but in a more responsible way. If you’re so inclined, work with your local state or national government and ask for some of the changes.

Jeff: Thanks for those two tips. I remember you talking about metal as well. What can you tell us about metal?

Amanda: Metal is infinitely recyclable. Please always, always recycle your metal. These are raw earth elements and so they are in limited supply. Also, the energy impact of mining, say, raw aluminum is so much more intensive than the energy that it takes for recycling. The soda cans, those bubble water cans, please always recycle them. If you’re in a place where there is no recycling, take it home with you and recycle it, please. It’s that important.

Jeff: Got it. One of the things you mentioned before was the can itself, you don’t need to crush it. Was I right in saying that or is it good to crush?

Amanda: You don’t need to crush it. Most things get crushed in the process of transportation anyway. It goes in the truck and everything gets smashed down, so things will naturally get moved around there. Our equipment for sortation, if it’s super crushed down, it’s going to be harder to pick. We like a good surface area so we can get a grip on it.

Jeff: Got it. What about composting? Composting is obviously a big part of our waste production, but any thoughts on what we can do there?

Amanda: For sure. Number one, don’t put your composting in landfill. It creates methane gases and that’s very bad for the environment. If you don’t have a curbside composting program, perhaps there’s something in your neighborhood for a community garden or perhaps there’s something you could do yourself. I know we just had Halloween and so everybody’s got those pumpkins that they’re getting rid of, please compost those. Do not throw those in your trash. If you super duper do not have a way to compost it just smash it on the ground and let the animals feed off of it. That’s better for the earth than trying to throw it in the garbage can.

Composting is wonderful. It doesn’t go in landfill, doesn’t go in recycling. It is its own stream. If you don’t have the offtake for it, contact your local government, try to get it. I bet there there’s community programs that you could contribute to.

Jeff: Nice. These are some great everyday tips. What about we’ve heard the term reduce, reuse, recycle, recycle being the last. What about reduce and reuse?

Amanda: It’s absolutely the correct order. It’s an old saying, but it’s still the correct saying. Reduce for sure, where you just don’t need something, where you have those single use especially plastics and you can make an alternative decision, please do. Reuse, glass is wonderful for reusing. Wherever you can reuse something, please do. Last is recycling. We’ve made it so that when you have no other option but to recycle it is more cost effective and more efficient overall to do it. That’s not going to be the silver bullet for how we really enable a world without waste.

Jeff: I’m curious as you’ve grown in your sustainability nerd status, your levels essentially. For me, you’re up here right now, but how has that changed your personal life? What are some things that you’ve changed as a result of getting deeper and deeper and deeper into this space?

Amanda: I feel wool dryer balls start to put you in a separate category, doesn’t it?

I absolutely do the collect your batteries, collect your electronics and your metals and once twice a year take it to a local facility where it’s more properly disposed. I was helping volunteer at a race a couple months ago and there was no recycling for all these plastic and aluminum cans. I held up a bag and had every runner drop their item into my bag and then took it home and recycled it. That’s the sort of sustainability nerd level I’m at, I think that’s a level of four out of five, maybe. There’s more I could do.

Jeff: Nice. That’s awesome. I would imagine that as this economy gets bigger and more domestic, there’ll be more jobs actually, more opportunities to participate in this space, which is meaningful. Any advice for those that want to get involved in this career that would be related to sustainability and recycling?

Amanda: It touches every aspect of roles that you can think of. We’ve got, just within AMP, we have teams who focus on government and policy, and helping government and policymakers understand how this technology can be applied and be used. We have an amazing marketing team, an amazing sales team, amazing tech team, amazing finance team.

I could go on, and on, and on.

Really, there’s no limitation to getting involved in any sustainability role. Whatever your unique talents are, if you feel passionate to connect that to this purpose, there’s something out there for you. Look around, and if there’s anything I can help with, reach out to me on LinkedIn.

Jeff: Amanda, it’s so great having you. Any closing thoughts for just the future recycling? Does anything come to mind?

Amanda: It’s going to require system changes. It’s going to require a lot of smart, passionate people to be part of the solution. Everyone who’s listening here, thank you. That’s the start.

Jeff: Awesome. I think obviously, the awareness and the education is a big part of that. We’re really excited about what you’re doing, and the future of recycling. Thanks for being with us and educating us all on how we can be better, and just a lot of things to look forward to. I really appreciate your depth and your passion.

Amanda: Thanks much. Don’t forget to recycle those cans.

Jeff: Oh, yes.

***

Jeff: The Future of podcast is brought to you by Fresh Consulting. To find out more about how we pair design and technology together to shape the future, visit us at freshconsulting.com. Make sure to search for The Future of in Apple podcast, Spotify, Google podcast, or anywhere else podcasts are found. Make sure to click subscribe so you don’t miss any of our future episodes. On behalf of our team here at Fresh, thank you for listening.