Podcast

The Future of Construction

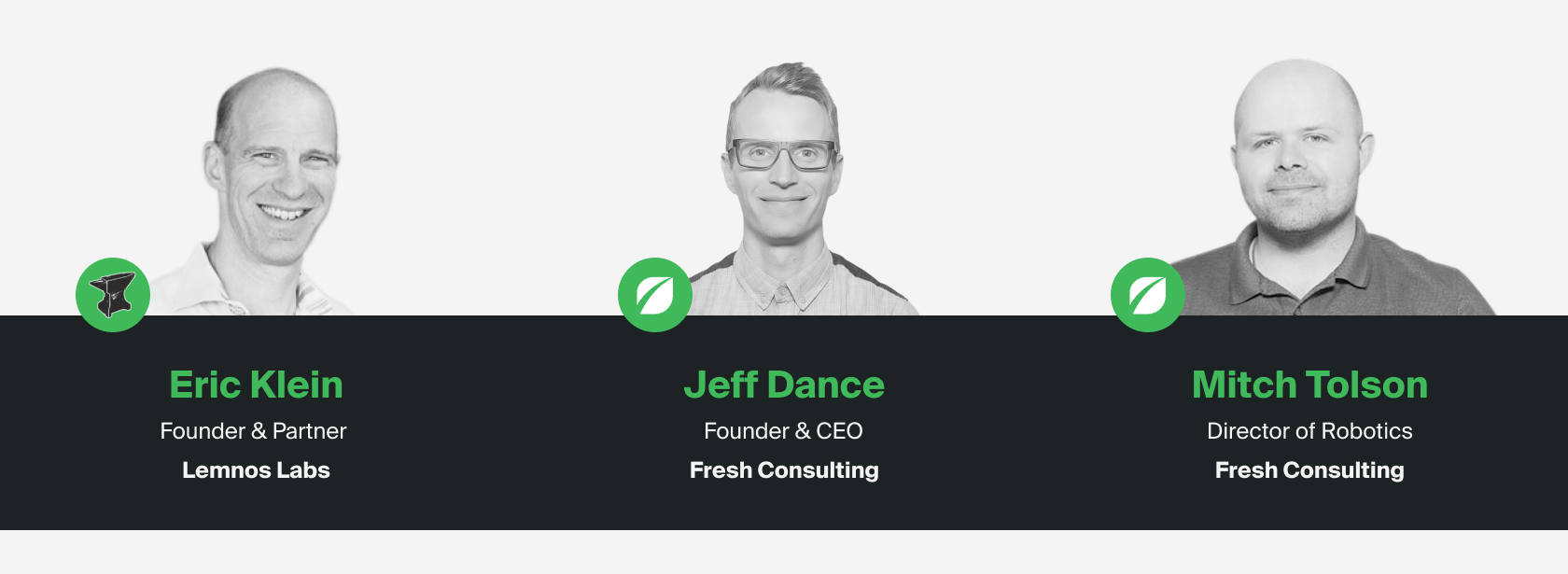

In this episode of The Future Of, we examine the current state of the construction space, its future direction, and the automation of industry tasks using robotics.

Joining us this week to explore this topic is Eric Klein, Partner at Lemnos, a hardware and software expert who has been an advisor to over 100 companies and built well-known products such as the Macintosh Powerbooks, first power PC Max, and the original Palm Pilot at Palm to name a few. Also joining us is Mitch Tolson, Director of Robotics at Fresh.

Eric Klein: We’re going to be able to see into things that we’ve never been able to see before, and we’re going to see a lot of problems that only a human is best capable of solving. The great thing I think when you talk about the future is that humans probably got some augmented equipment, whether they’re small machines or big machines, that will probably help them with those tasks so they can get it done safer, faster, and more efficiently.

Jeff Dance: Welcome to The Future Of, a podcast by Fresh Consulting, where we discuss and learn about the future of different industries, markets, and technology verticals. Together, we’ll chat with leaders and experts in the field and discuss how we can shape the future human experience. I’m your host, Jeff Dance.

In this episode of The Future Of, we’re joined by Eric Klein of Lemnos, and Mitch Tolson from Fresh Consulting to explore the future of construction. Gentlemen, welcome. It’s my pleasure to have you with me on this episode focused on the future of construction, and excited to have not only two leaders but to battle-tested engineers. Eric, if I can start with you. You’ve been a partner at Lemnos, a managing partner at Klein Venture Partners, prior to that, a VP for advanced engineering of Nokia, and a VP of Java marketing at Sun Microsystems.

I really like that combo of hardware and software experience that you have over dozens of years. Over that time, you’ve built some of the most well-known products and probably advised– I don’t know, how many companies have you advised over the years?

Eric: I think I’ve invested and advised over 100 companies, which sounds crazy. I was blessed to have the opportunity to work on some iconic products over the years. I worked on the original Macintosh PowerBooks and the first PowerPC Macs. I got to work on some of the original Palm Pilots when I was at Palm. Started a little video game company called Bungie, helped start that with some great folks, makers of the Halo universe. Yes, I’ve had a great career, but hardware has always been a big part of that and weaved into my narrative.

Jeff: Awesome. As it relates to construction itself, given our topic today, tell us more about some of the experiences in that space.

Eric: Yes. About six or seven years ago, my partners and I at Lemnos were really researching the future of labor. When we think about robotics, we think about applied robotics, which is a robot doing a particular task, not a general-purpose robot like the Jetsons had. We’re not quite there yet, but really looking at different labor areas and what could be augmented using robotics as robotics started to mature.

We finally got to the point where we could, from a cost perspective, build robots that could perform useful tasks. What we found was that construction was one of the more powerful areas for that growth, so we started looking at investments both in construction-based robotics companies, companies like FORT Robotics that was looking at construction towers and safety around that, and some horizontal applications like functional safety and security with a company like FORT Robotics.

We’ve had the opportunity to invest in the area. We believe very strongly that construction is one of those tasks. Again, if you look at it, there are so many sub-tasks that are necessary to bring a building up. Right now, there’s the opportunity for some of those to be automated. Not all of them yet but some of them. That curiosity and that data started us down a path of investing and learning and working with everybody in the industry around this.

Jeff: Thank you. Thanks for being here, just really excited to get your perspective from all that experience that you have. Mitch, if I can move over to you. Recognize you have 30 years of experience in the construction space and also the engineering and automation and software space. You’ve been at PACCAR as a lead of their product lifecycle management team.

PACCAR being one of the Fortune 500 companies, it’s one of the biggest in the space in trucking, and just one of the largest manufacturers in that vertical. Then at Microsoft, you’ve found and led the devices engineering, a services organization that supported over 3,500 people. Lots of experience there. Then now recently as Fresh Consulting as our robotics director. Not only that, my understanding is that you’ve devoted hundreds of hours to coaching STEM and FIRST Robotics with high school students, and you have four kids. How do you do it all?

Mitch Tolson: [chuckles] Thanks, Jeff. Happy to be here. I’m just focused on my vision. That vision is first and foremost empowering people, and then where I can, working on technology that saves the planet, and then someday exploring the universe. Along with that, it’s about tons of grit. You’re not going to find me on a cruise ship, instead, you’ll find me in my backyard tinkering on my riding lawnmower, converting it from petrol to an electric type of vehicle. It’s about continual learning and investing.

Jeff: Awesome. We all have different ways of having fun, but certainly appreciate your passion, not only to others but to the space. Into the future sounds a little bit more like Elon with his vision of getting to Mars. I love it.

Mitch: Someday. [laughs]

Jeff: Tell us a little bit more about your experience in construction. I’m aware of a lot of your experience in engineering and hardware, but tell us more about your experience with construction and how that started early on.

Mitch: My journey actually started when I was rather young through my family’s sign company back when I was six. It was installing signs and working through the permitting process and all of the electrical installation and mounting, and that’s expanded over the years. I’ve lived through it my entire life, and both of my dads are general contractors. Four of my direct siblings are journeyman electricians. Then I’ve also run my own site development company doing earth construction and stuff before you actually build the building. So I’ve lived a lot of these problems and I’ve also had many conversations with my siblings and peers throughout these years on what’s working for them and what’s not.

Jeff: That’s great. Well, it’s amazing to have you both here to talk about the future in general and particularly about the future of construction, given that it weaves in so many different spaces you both have experience in. As we look forward to the future, what does this space look like 10 to 20 years from now? When we think about the future, we think about the Jetsons. A lot of things probably come to mind but as experts in this space, as we project forward, what does the future of construction look like to both of you? Eric, I’ll start with you.

Eric: I think an interesting way to view that is just to take a bunch of technologies and project them into the future but overlay them into construction. You can do things, and I’ll start with a simple example. If you look at the future of mixed reality, the opportunities here are huge. Mitch, as you know, one of the big things is coordination on a job site, knowing that the job has been done right.

There’s this interesting term “BIM”, that somebody designed it a certain way but all through that process so many different tradespeople come to work on a project and you can start to imagine in the future where you’re going to be able to put on an augmented reality pair of glasses and really see the data behind the actual physical object. We talk a lot about digital twinning. This idea that there’s a digital version.

Well, the digital version starts with what we intended the building or the property to be but being able to look into that and see both what was expected and what’s reality, because on a construction site things change, change orders come in, things don’t necessarily always go the way you expect.

Another area is around advanced manufacturing, where we talk about a lot in the construction business about bringing more things pre-assembled to a site and also the ability, in the future, to start taking very raw pieces and doing sub-assembly manufacturing right on-site, where you can assemble walls, parts of the building, a lot of things, both more prefab coming in completely dialed into the original building specification or building things on-site, aka 3D printing as I think we back this out to a little bit. I’ve seen amazing stuff where you’re 3D printing but you’re using concrete. You’re using other substances. This isn’t just plastics in the future.

Then one that I think is near and dear to a lot of our hearts is robotics and automation is augmenting human labor and using robots to whether it’s the mundane or the thing that just takes– It’s 1,000 rivets kind of thing, bringing the robotics in to help accomplish tasks because one of the biggest challenges we face in construction is labor. It’s actually that we don’t have enough labor for the amount of construction that needs to get done. Augmentation allows us to get more done in an era where we’re going to be challenged to find enough people to build what we need to build.

Jeff: I’ve heard that there’s a national labor crisis in construction, and they’ve raised this up to the government. This is a serious crisis. This was years ago and pre-pandemic. Now, many industries are in that same space but I think has made it even worse for the construction vertical.

Eric: I always love to tell the story. One of my companies is Path Robotics and they look at the future of welding. In the United States right now, there’s a gap between 200,000 and 400,000 welders. Shipyards literally can’t do the work they want to do because they don’t have enough folks. The average age of a welder is 56 years old. That stat blew my mind. Up until many years ago, we honored the trade crafts, but there was a pivot in our society when we said white-collar jobs aren’t really where we want to draw and America backed away to a certain extent from vocational schools and from these amazing arts.

Now, the challenge is no matter how fast, even if we had people available to do it, to move them through the trades and to give them the skills that these folks have had and learned over 30 years. There’s almost no way to catch up. We’re going to have to use augmentation to help, again, build America and build the world, really.

Jeff: Thinking about that, it reminds me of the metaverse. Maybe we can go to work in the metaverse and bring some of these younger talent into the metaverse to work via remote welding. Hey. [laughs]

Eric: I think Mitch has got a lot to cover here. Construction it’s always been said it’s one of the most labor intense jobs, and it’s also one of the jobs with just the most subtasks. If you look at labor statistics data and economic data, it’s one of the air areas where our labor efficiency ratings haven’t gone up as much as in other categories. Everyone wonders about that but it’s because it’s actually an incredibly complex task across so many different disciplines to do, that automation, while it’s coming to it, and I think the industry loves it, it’s complicated to pull this off because of all the things that come together in terms of resources, people, and machines.

Jeff: I’d love to hear your perspective, Mitch. What does the future of construction look like for you?

Mitch: I resonate a lot with all of Eric’s comments. From a general contractor standpoint, the way I look at it is really looking at the problems that they face. As Eric was saying, it’s going to that, “How can I coordinate my crew and my subs more effectively at the right time within the building plan and the communication between different subcontractors, the suppliers delivering material on site, and really that connectivity?” The future of the smart job site is really about bringing connectivity to both your materials and your tools and your people.

The last thing I need is one of my subs forgetting their tool on the other side of the site and returning back to the site where they’re performing work. Then it goes into that augmentation, knowing the people within this space, they enjoy what they do but they want to do less of those annoying repetitive tasks. It’s, as Eric was talking about from an augmentation standpoint, “How can I understand if I’m installing an electrical panel within this wall? What’s the BIM say? What does code say? How do I maintain that context to perform that job right there within that local space and do that faster?”

Then it’s also things like when, again, as a GC, it’s making sure that did my guy show up to work today to get the job done. How can I augment and help those that do show up more effective? I think of this scenario of a drywall installation. A semi-truck pulls in, pallets full of drywall, you have two folks unloading onto drywall carts, then two folks walking that drywall cart into the place of installation, and then repeating that tons of times. It’s, “Well, what if instead of two people walking that drywall cart loaded with drywall, what if it’s one and it’s a robotic cart that then understands context of what the mission is, follow this person to the place of installation?”

There’s one less person that’s required on the job site, and going back to the comment of white-collar versus blue-collar, now there’s somebody at some engineering desk designing the next thing to augment those that are still on site.

Jeff: As we think about smart machines and robotics, what are examples of other things you think we’ll see that’s more commonplace 10 to 20 years from now?

Mitch: The way I think of it is if I’m a plumber or an electrician or an installer or whatever I am on a construction site, if I abstracted enough it’s about manipulation. I’m moving some object from one place to the other. If you watch a time-lapse of construction space, material is moving back and forth all the time. It could even be holding a drill. Screwing in screws, hammer, whatever.

When I think about the future and that tech and manipulation, I think about, “Well, in automation space and robotics we have robot arms,” but a lot of those robot arms were designed for industrial automation with sub-millimeter accuracy. Well, if I were to take that same robot arm and put it in construction, you’re paying for a set of features and performance that is unnecessary.

The folks on most construction sites it’s plus or minus an eighth of an inch. It’s a completely different measurement system. How can I take the tech of what we’ve developed for other applications and augment it and redesign and apply it to the space of construction that works that is reliable and helps them perform the job faster?

Jeff: More smart machines that basically can work in a messy environment.

Mitch: Messy environment. They’re tuned to this application, right?

Jeff: Yes. Eric, any thoughts on that, on smart machines that will be in the future?

Eric: Oh, I loved what Mitch was talking about. One of the things he said I think is mission-critical is this idea of communication. All of these examples it’s all about an underlying data, the ground truth. This is what we want to do. Then the data between, again, material, people, and machines to coordinate to make that base truth a reality. That communication, think of all the things that have to happen in the future for that to go well. It’s not only that we have Wi-Fi or 5G or 6G. By then maybe we’ll be at 7G or 8G. The point is it’s what’s happening inside of those communications channels.

Thinking about issues around safety. Making sure that everything’s going the way it’s supposed to go and securely. We don’t want anything to go wrong during this. Whether it’s for mal fees or just an error, we need– I love another phrase Mitch uses, which is overwatch. This idea of we also are going to have to build intelligence layers to go, “Hey, maybe this isn’t right, or maybe this machine needs to hold up here because we’ve got an issue with another part of the task that’s a little slower.” These are things that are coming that you might not think of, but all these layers have to come into existence for the future of construction work because they’re all a coordinated system.

I’ll play a little bit in the world today, which really is a hint to the world in the future, this example Mitch was talking about, we already have a number of companies building what we call follow-me robots. That the robot just knows I got one mission, follow that person. Wherever they go I go. Imagine now that machine is carrying hundreds of pounds. I love this drywall example.

It follows you around with hundreds of pounds of drywall. By the way, it’s delivering it out. You get onto the site and there’s a company called Dusty Robotics that basically runs out in the morning with robots and chalks out where on the floor those interior walls are supposed to be, which is a task right now. Someone manually runs around every day, and by the way, has to redo half the time because it gets scuffed up and marked up and changed. You get out there and you hit a Canvas robot. That robot’s job is to drywall up against existing studs that maybe were pre-manufactured.

I think if you start to imagine in the future a little bit, a couple of interesting things around that is I might be wearing– In fact, we’re very close and we’re starting to see first examples of exoskeleton suits, because that drywall is not light and the thing I’m as much worried about is lifting it. I want to make sure that the workers, “Hey, as Mitch said, we need to keep them on the site.”

What I don’t want them to do is to be injured on the job because they had to lift something and they just picked it up at a bad angle and they hurt their back. All of a sudden I’ve got an exoskeleton suit and I can carry twice the weight, but I can do it safely and the worker is protected in that environment. They’re wearing XR glasses and they know where the electrical is behind it. Even their basic tools, we see this on manufacturing lines today. I’ve got new torque wrenches and stuff that are dialed in so I can’t put too much rotational speed on a screw. The machine is instrumenting and knowing that in fact even down to that level that things are going the way we expected them to.

It’s literally from your hand drill all the way up to the material around you as the worker, to the machines around you. In the simple case of drywall, we can do it. What this is going to allow us to do is going to allow us to put more drywall up more efficiently, more cost economically than we did before, which is really what we need to do in just this one small task inside of a massive construction chain.

Jeff: So much coordination and so much sequential steps that the faster you can do one step the faster you can do an overall project, right? The better or safer you can do the steps the better the project will run, but it’s all coordinated. Right now it’s coordinated by hand, right? It’s somewhat of a big mess and things constantly moving around, but a lot more sophistication around the coordination happening in the future. Then a lot more machines supporting and augmenting people doing those tasks.

What about large machines? We’ve talked about some smaller machines. Do you envision any larger machines? Obviously, we see a lot of big construction-oriented machines. Can you speak to larger machines at all?

Mitch: Building off what Eric’s saying, imagine you have the automated interoperability of context. Let’s just call that some engine or service in the background. Going back to that drywall example and answering your question, Jeff, if I’m the person that’s in the exoskeleton, imagine I have context of, “All right, I know where that person’s at in that room. I know that they’re installing drywall.” I’m projecting the lines of the studs, and I also have in my hat saying, “Oh, your next drywall cart is arriving in three minutes,” so hurry up, right? To overall increase flow. Then that back channels into, “Well my telehandler outside of the building is going to have to maybe drive, unload the semi-truck to the place of bringing it into the building.” Now we’re connecting these larger machines into this entire automated workflow.

Eric: One thing that’s really easy around construction is you have to remember with construction, on scale, it’s both micro and macro. When I think of sites, sometimes I think about 100-acre sites. You were talking about large machines, 100-ton mining machines have been rolling autonomously in the outback of Australia for 20 years practically. In fact, they’re getting ready for their second wave, their second generation of fully autonomous vehicles. I think some of that knowledge comes to, again, these large construction sites which are measured in tens of acres and multiple buildings and the complexity there.

To Mitch’s point, you got a lot of large machinery coming in and, in some cases, whether it’s all the way through your front loaders, your big machines that are doing site preparation, to the smaller machines that are working on the inside of the building. Think of all those cranes. A friend of mine– Again, we have a company that was in this space in the crane side of things, and he’ll say the biggest safety innovation of the last 60 years in construction cranes is the walkie-talkie. They still don’t have high-end surveillance cameras systems that tell those operators what’s going on. In a lot of cases, it’s people on mics trying to coordinate this on sites.

There’s a lot of room for improvement on these processes, but again, the scale of some of these machines is massive. It can be a couple 100 feet in the air. They could be a 50-ton machine, all the way down to your hand driver that you’re using to put things into the wall. Think of the scale. All of those, when you think of a site, it’s thousands of devices. It’s interesting because one of the things is when you talk about tracking them, some of these high-value items, by the way, throughout their entire life cycle from the moment they’re made to the point they get to the construction site, they’re an asset whose value means that they’re being tracked dynamically. They have their own tagging system.

To be clear, when drywall comes in, it’s not really tagged so think about the building. The site itself almost has to have its own vision systems so that it can see the untracked. I know there’s a lot of companies working on better tracking for people so that we understand where the people are relative to the machines, but it’s also seeing the material moving around. As Mitch was saying, so much material moving at the same time in the same room in the same floor of a building, in fact, moving to get out of the way of other material that’s on its way in.

If they’re not tracked actively, if they don’t have their own tracker built into them, we’ll probably end up having to use a lot of vision systems to see that. Then, once you can see it, you can start to say, “How do I optimize it?”

Mitch: A lot of that we call perception engineering. Developing those classification models on the set of material inventory that these models haven’t been developed yet. We need an army of folks to go build out those so that, as Eric is saying, you can understand dynamic contexts in the overall flow of a construction site.

Jeff: Autonomy requires awareness of context. For the last 10 to 20 years, we’ve been talking about smart this or smart this because it’s connected to the internet, but it truly hasn’t been smart. It hasn’t had its own self-awareness, or it hasn’t been able to make choices between different contexts as the environment changes. As we move into the future, with so much more AI and connected systems, these machines or materials having these mini-brains, where they’re making decisions and trying to connect into the larger ecosystem of building things, knowing that there’s a lot of micro and macro in that equation.

Eric: Autonomy in construction, it’s interesting because you’re not only saying autonomous. We love to say autonomous like it’s just thinking on its own, it’s in its own little bubble doing its thing. That’s true, but it needs to be connected, and smart is almost the right word here because smart says, “Hey, you’re thinking about doing this and you may stop for that but you’re not aware of the five other things going on that we’re coordinating. You may see something where you think you need to stop, but I’m actually going to stop everything around you so that you can go through because your material needs to get going.”

Smart is really about taking automation and really, again, applying the business logic to it. Maybe there’s a word for this. I don’t know if it exists. It’s like construction logic, which is the business logic of the site of how things are done, which humans are great at, and we’re going to need to teach a lot of things to work with us on.

Mitch: When I think about the future of construction and the word augmentation, how do we expose that information to folks so that they’re a more informed decision-maker? As I look at the now, soon, and later within the space, now we’re starting to work through perception engineering and really making intelligence out of that data. Well, after we start exposing that data set, the next wave I see is what I call prediction engineering.

Now, it’s like looking at, “Okay, here’s the historical trend, what’s actually going to happen in the future?” If I’m a GC, I can call up my sub and say, “Hey, that material is not going to be ready for you. Don’t deliver today, deliver it in three days.” Instead, I’m going to call up my other sub and say, “Hey, can you come in today to perform your work?” You’re optimizing that entire flow.

Jeff: We’ve talked about the role of smart machines and automation and the micro-macro coordination that happens between all of this and humans, I’m wondering how humans fit into the mix of all of this.

Eric: It’s funny. I’ve worked with a ton of companies in robotics and the funny thing is when you ask the trades folks– There’s maybe a false statement that says that unions and tradespeople are afraid of technology. In my experience, if it makes their job easier and it gets them out of doing that mundane task they have to do 100 times a day, they’re consumers of technology. They love it. Again, it’s got to be approachable. It’s got to make their job better, faster, easier, because with labor– I’ll go back to this welding example. When I talk to the owners of these companies, what they want is they want their experienced welders working on the really hard problems.

The ones that we cannot automate today, so automation’s job is augmentation. It’s really about doing that mundane task that nobody really wants to do but we’ve got to do a lot of it. Sheetrocking [chuckles], just putting it up. Again, does that say that we’re not going to have a master person getting there for finish and for, again, difficult problems? Or when a rework comes in, you’re like, “Oh my gosh, how are we going to solve this problem?” The human brain is just– We can’t match it. When you talk about the people inside the industry, they’re excited to bring this technology to bear.

Mitch: I don’t know how many times I’ve been on top of a ladder and I’m pulling Cat 6 wire across a drop ceiling and I’m using fish tape and it’s hitting the little ledges. Man, after 30 minutes, it’s just frustrating. This is where it’s like, “Okay, if I had a second person, but they didn’t show up today, but if I did, they could be on the receiving end and help me pull that.” Instead, if I had technology to help me perform this task, let’s say I had a little micro drone that I just pull out of my pocket, tie the pull string to, throw it into the drop-ceiling space, it then had a perception engine on board that said, “Oh, I’m going to this spot.” It flies over and now I have my pull string. Now, my job’s done in a matter of minutes.

It’s things like that, from the little micro-tasks as Eric was saying, how do I help those tradesmen perform that job faster and easier?

Eric: That’s going to be one of your hidden– Mitch, you were talking about perception. If I zoom my camera back out, you’re going to see all the holes in my walls as my electricians had to try to reverse figure out where everything was and how to get around a bunch of studs that they didn’t think should have been where they were as they curse some contractor many years ago. We talk about the future. We’re already working on stuff with millimeter-wave technology, and it was pioneered by the military many years ago, where we can see through walls now. We can see things that we couldn’t see before.

I love to describe the world where you can bring up this electronic BIM and you can see exactly what the building is supposed to be, but for the hundreds of millions of buildings out there right now, there is no BIM. When we’re talking about new construction versus renovation, we’re going to be able to see into things that we’ve never been able to see before, and we’re going to see a lot of problems that only a human is best capable of solving. The great thing, when you talk about the future, is that humans probably got some augmented equipment, whether they’re small machines or big machines, that’ll probably help them with those tasks so they can get it done safer, faster, and more efficiently.

Jeff: Got it. You talked a lot about augmentation and integration as a theme. Even in manufacturing, there are certain situations where you can have a lights-out environment. There’s machines working all night long and they’re working together to automate something. More programmatic, a lot more structure there. Do you envision an environment where machines could do that in the future or are humans going to always be in the mix?

Eric: Well, I can’t tell you how many venture proposals I’ve gotten, which is the magical, “We’re going to 3D construct your building right in front of you. You’re going to come in the next day, and literally, it’s move-in ready,” and I’m like, “Hmm.” If you look at the progression– I liked how Mitch was doing the steps along the way. Right now what we’re seeing is the first time the robots are actually on pilot sites doing things like chalk marking or putting up sheet wall or looking at construction crane safety and things like that. Singular tasks, singular robot.

I think what’s going to be coming in the future is all of a sudden we’re going to start stringing these together, where the robot’s going to do one task. Maybe, for instance, a low voltage person’s got to come in behind them to do some finishing work or do some other work and then another robot might come in. Even for the person who’s doing the manual work, maybe they’ve got a companion robot bringing all their tools and all the resources they need, but stringing these things together is going to be the next thing that’s coming.

I think at major conferences, we’re all starting to talk about, “Holy cow, now that we have a couple of robots doing different things, how do we coordinate them?” Getting all the way to lights out, I think if you’re being realistic, it’s the goal, no question. The idea that the robots just come, and literally, it’s all certified. It’s just ready to move in, but in the 10 to 20-year thing, I think the next big thing that happens is the starting to coordinate heterogeneous robots doing different tasks, where the humans and all that material is still 100% engaged.

Jeff: Definitely, we’ve heard the role of robotics were dirty, dull, and dangerous, these situations that aren’t ideal for humans, to begin with, but it’s interesting to hear about just expected integration between all the coordination and the chaos that happens there. We would expect there’d still be, we’re augmenting, we’re integrating, but we are certainly not replacing. Just sounds like helping them do more meaningful work and not the repetitive work that isn’t good for really any human experience, right?

Mitch: That’s very fair and also the problem is, we need more product managers to help define the requirements that have never been defined. From a robot standpoint, if I have an arm mounted to a mobile robot base, I might ask from an engineering standpoint and say, “Well, how many times can I hit the wall?” If you ask the customer, they’re going to be like, “Zero times,” but the reality is people accidentally run into the wall. It’s just not recorded, and it’s not tracked. It’s about what is the thing, the criteria that you have to design for now, and then what are those things that you have to look at later?

Eric: There’s so much teaching in this business. I was talking about the welding example. There are a lot of times when this company Path Robotics, as they started working on more complex welding tasks, the robot, through machine learning and a bunch of techniques, would come up with a way to do it. It would run it and it would fail and we would bring the experienced welder out there and the welder would be like, “You’re fighting gravity. Why would you do that that way?” Whether it’s the product manager or the actual tradesperson or the engineer, there’s that transfer of knowledge.

We’ve all had that situation, you run a power drill into a wall. We know by feeling what we’re going into, right? We also have that subtle intuition of when we can go too far and when we can’t. Those are things to the point that it’s hard. You have to learn those things. Product managers have to go out in the field, people feel that user experience folks have to go out in the field and learn what’s really going on so that we can pass that type of knowledge into the robotics chain so we can start to go, “Well, what would we have to put into the tool to sense that rotational torque is coming down?”

“What’s going on?” “Okay, I’m getting a whole bunch of numbers back off of a sensor but what the heck do they mean and what do I do with those numbers?” In construction, there are some nuances to that.

Mitch: What Eric is saying, going back to his drilling into a wall, as humans, we just get a sense of what that means if, “Oh, crud, I just hit some wire behind that. Oh, man.” When I look at that from a programmatic standpoint, as an engineer, I have to build a semantic interface. Then I have to say, “Okay, well, what’s important to the tradesperson that’s on site if it gives me a data point and says ‘oh, over-torque’?” It’s like, “Well, wait, what does that mean?” Then we have to have data scientists that come in and characterize what are the different behaviors of this operation to then say, “Hey, 80% probable that we hit some wire behind this?”

“Okay. Alright. I’m going to have to cut the drywall and go in there and inspect it now,” versus over-torque. I can’t do anything with that information. Then the interoperability there is that as we look at automated machines and humans working together, it’s how do I translate that data between these different interfaces to, again, maintain that context and the overall coordination and communication between them?

Jeff: As we think about the construction space, recognized labor shortage is one of those serious problems right now, and it’s not getting better, but if we look back in time, it’s one of the spaces that hasn’t moved as fast as other industries as far as advancements. You talked about the walkie-talkie with crane operators as an example, or smart radio. What are some of the macro forces right now? We’ve had this pandemic, we have an even deeper labor shortage, what are some of the macro forces that you think will move this space faster in the next 10 to 20 years?

Eric: I think one of the things you can look at as an example, single-family home starts. For years before the pandemic for reasons that are various, new house starts were way down. All of a sudden, we have a pandemic, and that exacerbates situations. Everybody suddenly wants to get into a home and have some more space around them. It’s amazing how these things fit together, and of course, I want to crank up the number of new starts but we at a macro-level also just migrate immigration patterns, government policy, diversity of jobs says there are less people available that do the work or want to do the work or available to do the work.

I think all of us have tried to get a hold of contractors over the last six months and they’re the most valuable resource on planet Earth, but we’re all in a system together. It’s the combination of do we have enough vocational schools. Even if we say I want to turn the switch on tomorrow and get more welders, more electricians, more folks to work on drywall, and you name the task, journeymen, whatever it is. Number one, we have a lot of pressure on the system, and then now even if we crank it up, it’s like the modern supply chain. It’s not that resilient. It doesn’t spin up that quickly.

You were saying what’s going to accelerate it. It’s very clear that in terms of building starts across the world are going up and we’re often rebuilding buildings thinking about the Green Revolution, and really revolutionizing and refitting buildings and building new buildings that we’re going to need to do for climate change to be successful. Those buildings generate a lot of the core emissions and can be contributors both of good and bad. I think you’re seeing both population changes that are pushing for more construction work to be done.

I can tell you from the venture community’s perspective, we recognize this. What we do is stare at macro trends. What got me into this was five or six years ago, we were looking at the Bureau of Labor Statistics data. The government has literally built a document that explains every job in the United States what manual dexterity is required. I could then map that against robotics trends and tell you when things were going to be possible. The venture dollars know that at the macro level there’s a huge pull towards new construction and making construction more efficient.

We know labor shortages are there, and if we can use the data properly, we can say, “Wow, we’ve got to put more money into robotics and augmentation and all the systems around it,” communication, safety, security, transportation, energy efficiency that go into what is at the end of the day your five-story office building or your single-family home.

Mitch: You mentioned that constructions lagged behind, and there’s many reasons for that. One that comes to my mind is when I compare it against other industries, I’ve helped set up manufacturing lines acting as an MPI engineer. The variance there is, those manufacturing lines, it’s a highly deterministic system. You have a discrete product or operation that you have to optimize that takt time. How can you do that? It’s all about repetitiveness. When you go to construction, it’s highly unstructured environments.

As a technology, what we’ve lacked is, again, perception engineering. Understanding the context of my unstructured environment to then develop classification algorithms to then translate that into a workflow or a set of tasks that I can perform dynamically.

Eric: If you back up to go forward, in the last 5 or 10 years, think of what we’ve got that we didn’t have 5 or 10 years ago that we can apply to construction. The boom around ML, machine learning, perception systems, just the quality of the sensor data that we can now capture efficiently, improve communication tools. Robotics, our ability battery, just propulsion and energy management, huge improvements. Electric motors. Thank you, Tesla, and a whole bunch of other folks. Thanks, Elon.

ESCs and electric motors, 5 or 10 years ago if you tried to source 100 of them, you’d get 99 different motors back, but as we drew demand into that segment because of EVs and other new tools, all of a sudden quality and quantity went up. All of these things are facilitating– They’re the baseline that we need so now, to Mitch’s point, we can start to say, “All right, we can capture this data.” We’ve made massive leaps forward in ML, but we’re going to need a whole nother jump forward because the complexity of a construction site and the types of things we’re doing.

Soft robotics. We’re going to make massive improvements in how we control machines and how we perceive things, but the base is there and you can just take a line and keep going with it, and that’ll take you to the future.

Mitch: I think also is that as we look from a control standpoint, we had classic control, feedforward control, MPC controllers that even helpful for whole vehicle modeling and control, and now I think it’s more we’re developing the tech around DRL, deep reinforcement learning. That is something that’s interesting that now if I can simulate my environment, I can look at those different hyperparameters and tune, “What are my termination points? When have I failed this particular task?”

I can throw 20,000 simulations variations of that and train a model with something called machine teaching as if I was the journeymen to apprentice. Now, the simulation is teaching the apprentice how to perform a mission or a task, and now we can take that model and deploy it to our automation systems. I would expect to see more and more of that enter into the construction space on these discrete tasks.

Jeff: I hadn’t thought about that. It’s basically simulating the workflow-

Mitch: That’s right.

Jeff: -and knowing that it’s an unstructured environment and being able to predict.

Eric: I loved it. I was talking with a site manager, and we’re talking about safety and security and he said, “Well, security for me up until very recently was, I knew that the keys for the front loader were in the visor up top.” That was their idea, the physical security, could someone just jump into the thing and drive it away, but all of a sudden, if it’s now connected and gaining increasingly intelligent, they’re like, “Holy cow, this is an all-new ballgame for us, and it’s not something we’re as familiar with, but we’re going to need those layers as well.”

Everything in this process is getting uplifted, and if you just look back not that far, you’ll see a very different world versus the one we’re in today. When you go into the future, you can just continue to say it’s going to get more connected, and we have the opportunity not only to make advances in terms of security but also safety. Again, we talked about exoskeletons and a whole bunch of other tools designed to keep that worker who’s so precious to the construction industry, safe and secure in what they’re doing on a daily basis.

Jeff: Yes, I would imagine lots of layers of safety, especially given how many connected big and small machines are. We don’t want someone tapping into the ecosystem of all those coordinated machines and playing around, right?

Eric: I’ve seen great stuff for folks in the electrical business. A bunch of folks have pitched us about personal devices you’re wearing that detect, for instance, you can pick when it’s high voltage. I can sense it far before you’re there, enough time to let the worker know, “Hey, that is an undocumented line here, we don’t know what’s going on but you need to stay away.” Sensing system perception is not only for the machines, it’s for the workers.

Jeff: It makes sense. We’ve had some experience working with user experience in robotics and how you communicate to each other, but beyond that, if there are systems recognizing the danger for you and alerting you because you’re both connected essentially, then I could see that being more predictive and avoiding situations before versus just knowing what each other is doing and where they’re going.

Mitch: If these things are connected, imagine there’s an IoT device of sorts, let’s say an e-stop, that somebody chest mounts, and so it’s both that situational awareness around you from some predetermined perimeter, “Oh, there’s a scissor lift coming towards you from your left,” maybe it vibrates a little bit, “Hey, be careful over your right shoulder,” or it’s, “Oh, man, this thing’s coming out, man, just stop it,” and boom, within region those automated devices stop or pause.

Jeff: Some of the companies that we see, one thing I guess I would say I’m learning is that there’s a lot of movement now. There’s a lot of companies involved now. Who do we see helping lead this space into the future? There are so many different players now, maybe it isn’t just one, but can you guys think of some companies that are really leading out in the space and in others? It’s a combination of companies that are playing in the construction space but do any come to mind?

Eric: I would start. I think it’s a federation that’s going to make this a reality. I’ve had the opportunity now to work with some great GCs, some of the people who are on some of the largest sites in the world and the largest number of sites. The funny thing, again, they have their own technology teams because their challenge is integration. They’ve got to bring these in and fold them into their existing processes, so you’re seeing some great GCs out in front of this effort.

Then down at the technology level and at the robotics level and things, you see folks who are doing things like if you look at what Clearpath is doing in terms of robotic—the propulsion and chassis that are going to drive. Folks like Clearpath and Ghost who are saying, “Look, construction sites, by the way, moving around them is not a simple task.” Cars love roadways. We as humans are only okay driving and we get lanes, right?

Jeff: Yes.

Eric: Unstructured environments and with every environmental condition, it can be 20 degrees below to 115 degrees with directing, oh my gosh. Think about that going on. There’s folks working at that level. At every layer, you’re seeing innovation, and then you see people who roll it all together. Again, I always love pointing out this company Dusty Robotics, Tessa Lau’s company, she went into construction and said, “What do you guys need?” By the way, Mitch, I know one of the things they looked at was sweeping. It’s mundane. It’s like, “Why would I build a robot to do that?” It’s actually a really big problem.

Mitch: It is, yes.

Eric: Then another problem they found was, again, just marking. Marking up the sites and making sure that everything was accurate. I see lots of examples like that, but you almost have to think of it as a whole chain going on, that the GCs, the trade unions themselves are very engaged with robotics companies saying, “Here’s what we need you to do,” as opposed to you coming as a master technologist who thinks everything about technology but you have no idea what it’s like to actually drill into a wall or do this one task. There’s coordination, but I think you are starting to see some really amazing companies.

Everyone loves talking about Canvas Robotics. Again, the sheetrocking company. Amazing story there around efficiency, but those stories pop up all throughout what I’m going to call the construction stack.

Jeff: Yes. The new type of tech stack for the future of building real things.

Eric: Yes. Look at what Microsoft’s doing around HoloLens. We were talking about XR at the beginning, they’ve said, “Look, let’s focus in on enterprise applications.” As much as we all want to come home and play cool games and deal with our Pokemon, it’s great to be in the field with a level of knowledge in terms of repair and construction that we’ve never seen before. I think you’re going to see folks like that continue to pile on with a very industrial and enterprise focus.

Mitch: I’m interested in companies that really open up additional optionality for future integrations to occur. Things like Wingtra, where they’re really looking at site surveying. It’s about recognizing the variance between the BIM and the actual what’s implemented, and then that gives insights into what I have to go fix or how do I plan out my next set of work. Then that falls into companies like Autodesk, they have Revit, right? They’re owners of BIM, if you will. How do they build more interfaces so now this whole interoperability-connected ecosystem can query that as the master source of true plan of record for that site?

Eric: We’ve got a company in our portfolio that does just this, looking at basically going on site. The thing we love to say is, “You get one chance to look at the foundational work and all the piping that gets sunk into the concrete because the minute that gets poured, that’s it. You get one chance to know what’s right or wrong versus what was expected.” I can see through the concrete afterwards, but to pull it back out costs weeks and millions of dollars on some sites.

One of the biggest costs in construction turns out to be the cost of failure and the litigation that’s associated with most sites because something didn’t get right, so that idea that there’s, again, this ground truth, this BIM, sensing that and catching those things before they happen is a huge part of this model and there’s a bunch of companies looking at– Again, to Mitch’s point, some of these things are measured in an eighth of an inch, and some of these things are measured in tolerances all over the board, but the higher fidelity we can capture something the more likely it is we can figure out what to do.

Again, there is much in construction, it’s like hardware, right? It is. Once we do it, to undo it is way more expensive than doing it right the first time. I can’t hit uncommit on the software tree button and magically pull that concrete back out or pull all that rebar out of there or do whatever it is I’ve got to do to fix whatever problem that we should have seen.

Jeff: One thing that strikes me, and thank you for all the expertise shared so far, is that a lot of the future we’re talking about is already here today in sort of a baby form. It’s like it’s already here and yet it’s not quite smart enough yet, or isn’t quite connected yet, but a lot of the pieces are here, the ingredients are here as we think about the future. If we re-center on the future of construction and the future of humans in that world, how would you summarize your thoughts around that?

Eric: I think there’s a word that Mitch used and we hear it all the time in the world’s we live in, which is systems engineering and complex systems thought. The construction site is one of the most complex. I get to invest across all different markets and it’s one of the most complex difficult environments I’ve ever seen, which is exciting. I love it, but I think the future, what unlocks this, is systems-level thinking. As you said in the baby steps, we bring all the Lego pieces to the party, but you need the Lego Master Builder to put it together. I see those Legos back there, Mitch, in your background.

Mitch: They’re special.

Eric: The interesting thing about that is really to the point that the systems engineers today are the construction workers in many ways, the trades, the GCs, that knowledge in their head of how that system works today, we have to bring our new augmented tools, our smart tools, and they’ve got to fit into that system first and adapt it as it moves along. You can’t disrupt construction. We can’t slow down. It’s got to fit in from day one, and it’s got to get more intelligent about all that knowledge that only the welder knows, that only the journeyman electrician knows.

That knowledge, if we can bring that out, that systems-level thinking, both at the functional level of, “Hey, I’m an electrician. Here’s what I need to know,” and at the whole building level, I think that’s a big part of what’s going to take us into that next era. It’s not just better LiON batteries and better camera sensing technology. It’s going to be taking the knowledge of how construction sites work and transferring that so that we can make more digital systems to go along with what continues to be one of the most physical jobs that we have in the world, right?

Mitch: Yes. It goes back to the whole coordination of context and what Eric was just saying about the systems engineering of it as we try to solve for these problems. It’s really going back to the first principles of that. The trades folk they might not actually understand why they do what they do, but it’s going down to that, “Okay, if I’m a framer and I have to nail in some nails into these 2-by-4s, it’s really going to, ‘okay, don’t just think about the actuation of swinging the hammer but where’s that person grabbing their hammer?'” “Oh, it’s off their right hip in their tool belt.”

What’s the size of that tool belt? Where’s that tool belt located? Is it right or left or what? Then we think about how that has context to that whole problem, the whole workflow stringing together. Then you expand that out to, “Well, why does a person know they have to go hammer nails in that spot?” It’s connecting in that data set, the context of the whole system, into helping them understand, “Oh, I have to nail and this a load-bearing wall. Here’s how it has to be designed rather than built up rather than the other wall.”

Jeff: To wrap up I have two final questions. One is, what would be one of the coolest problems you think that the future of construction will solve? That could be one of the problems I guess we’ve already discussed. That’s one question. Then the last is, if you were to give yourself some advice to your 21-year-old self, what would that be like? We might have some listeners that are listening to this and would appreciate some of that advice.

Mitch: I’ll answer the second question first.

Jeff: Okay.

Mitch: My 21-year self advice. I don’t think of this question in terms of if I were to go back in time what would I do different because I am who I am today and I’m happy with that, but if I could say one thing, it would be, “Take the time to develop clarity on your mission and stay focused to that and work on developing your key talents and strengths.” Then as I think about coolest problem. I would say it’s really about construction. There’s a lot of elements of speed. How do you do things faster? It goes into this whole growth mindset of how do I explore a mock-up test a highly iterative scientific method. If I can perform my work faster I can learn faster and then I can improve it even further, right?

I think just by having that context that helps improve the coordination, we can get higher cycles through to help us learn even faster.

Eric: From my side as an engineer, the thing I always hate doing and we all do it is you do something and you do it wrong like nine times and then you finally get it right. What I know about construction and the business behind construction is that mistakes are incredibly expensive. The thing I’m most fascinated with, I invest them in a company called SolidSpace, and what they do is that millimeter-accurate LiDAR scan of buildings at key junctions to make sure that what is done it looks like the BIM, because sometimes millimeters matter, sometimes inches matter.

I’m a huge fan of this idea of trying to get a better perception of construction so that we can stop with the simple mistakes. If we’re going to make mistakes, they should be ones that are really complex. We shouldn’t get tripped up on the simple stuff. To the future 21-year-olds of the universe, I always say I would tell them to be curious even when it’s not fun, which is to say when you go to university as an engineer I got to spend a certain amount of time in the business school and there were days where accounting was just dead boring to me.

I just wanted to go back to my terminal and write some code, but later on, what you find, and I think we’ve been talking about this this entire time, everything is a business, right? There’s economics that shape engineering, right? Construction is one of the biggest applications of economics. The amount of capital deployed is massive. Understanding some of those things you’re like, “Why am I in accounting? I’m an electrical engineer. I’m a mechatronics person. Why the heck did they send me over here?” Later on, you’re going to realize that what you build is part of a bigger system.

So even though it doesn’t make sense at the time or it doesn’t seem as much fun as you think, the depth or the breadth of knowledge outside of your core functional discipline it will pay off in the end, it just doesn’t make sense maybe at that moment, so pay attention in that class. Don’t snooze and study for your next EE class.

Mitch: I call that grit. Have the grit. Go through the hard learnings. Keep pushing forward.

Jeff: Thank you both. I guess one thought I would add, building on things you guys have said earlier, is just the notion of safety, the future of construction, the technology we can bring to safety, and how that can be better for the human experience, whether that’s exoskeletons or monitoring or predicting to keep us safer. We know that’s a big topic in construction, but one we can do a lot better at when we get smarter. That’s something that struck me from our conversations.

I wanted to say thank you. Thank you, Eric. Thank you, Mitch, for all of your insights and your wisdom as battle-tested leaders and also engineers and people that have been really well connected to the construction space to bring us all this thinking. Loved hearing your thoughts, and thanks again for being on the show.

Eric: Thank you.

Mitch: Thank you, Jeff. This has been great.

Jeff: The Future Of podcast is brought to you by Fresh Consulting. To find out more about how we pair design and technology together to shape the future, visit us at freshconsulting.com. Make sure to search for The Future Of in Apple Podcast, Spotify, Google Podcast, or anywhere else podcasts are found. Make sure to click subscribe so you don’t miss any of our future episodes. On behalf of our team here at Fresh, thank you for listening.